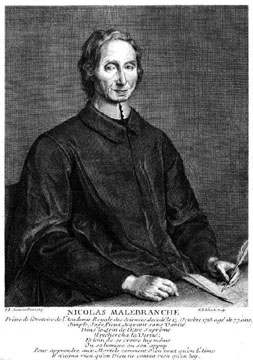

Where False Starting Points Can Lead - A Few Thoughts on 17th Century Idealism - Excerpts from "The Search After Truth" by Nicolas Malebranche

Stephen Alexander Beach

(1288 Words)

One of the major consequences of Descartes philosophy is that when one posits the first metaphysical truth, upon which all other truths depend, as the act of thinking, then human subjectivity becomes fundamental to philosophy. This always encounters the problem of transcending the supposed barrier between the thoughts of the mind and the reality of the physical world. Descartes must appeal to God to verify the truth of the physical world which he perceives. Bishop Berkeley, likewise, follow the same track, though takes it further, saying that God is, essentially, simulating everything we know and experience in himself. Nicolas Malebranche follows in this tradition, and takes it yet further, holding that God supplies the action that man desires to complete in the simulation, so to speak.

God As Cause Of All

For Malebranche, it appears, from the excerpts of his work The Search after Truth, that man is a mind trapped helplessly in a body. The idea of mans’ inadequacy is much stronger than in, say, his contemporary Pascal’s philosophy, as Malebranche views man as almost completely powerless. (171) Malebranche, talking about mans’ nature, says that it is God that draws and pushes man to seek the good (which Malebranche says is God, even when man is mistaken on what the good is). It is God who brings man all his knowledge, his sense perceptions, and who executes the desires of his will. Man does not have to power to truly do these things. All of these are from God in a direct and mediating way. not in any type of Scholastic sense. Again, in Malebranche’s system, men know everything through God, they see the world only through God, his desires are from God, and that God then executes what man wants to do. (172)

And so just as Malebranche had a strong view of mans’ inadequacy, this requires a corresponding idea of God as cause also. Since man is incapable of doing anything without God, God must then be the cause which makes up for mans’ inability. Malebranche says that one cannot be fooled by one’s natural experience of being a cause of their actions, but must use reason to come to the real truth that they are not causes at all in the proper sense. (174)

Why does he come to this conclusion? Well, this is due to Malebranche following Descartes inversion of the starting point of philosophy, leading to his idea that there are only three kinds of things; minds (like the res-cogitans), bodies (like the res-extensa), and God. So, like Descartes, beginning philosophy from the mind leads to a serious problem of how minds or bodies can affect one another. While Descartes tries to reconcile this by saying that the mind and body meet in the brain, Malebranche says that he does not see any way that minds or bodies could relate or be the causes of anything; to be a true cause of something is only possible by God, who is infinite and can actually affect what he wants to do. “The motor force of bodies is therefore not in the bodies that are moved, for this motor force is nothing other than the will of God.” (171)

Basically, Malebranche explains his system by saying that when one wants to move or do something, this is only the “occasional” or “natural” cause for God to affect or honor one’s desire to move or cause something by actually making it happen. It is not really the person effecting these acts, but God. So God, for Malebranche, must be the efficacious cause of everything that makes up for man’s inability to move anything because using Descartes’ ideas of minds, bodies, and God, only God has the power to cause anything directly. (171)

Malebranche tries to show this in the example of man moving his arm. He says that if man cannot know how exactly he moves his arm, or how by the power of his form he can do it, then, therefore, it only makes sense that man only wills to move his arm while God is the one who really executes it. (172)

Implicit in this philosophy is that Malebranche has done away with any traditional notion of substantial forms which exist outside the mind. And so to communicate and be a true cause of another is a prerogative only of the divine nature, and we cannot claim everything in nature is a cause and divine. (170, 171) Therefore all causes, and everything that happens, is really executed by God. (171)

It does not seem from this excerpt that Malebranche gives any true philosophical proofs for these beliefs. When he tries to back his beliefs up, he falls to making an argument from Scripture or theology. He makes the argument that because of sin man has fallen from God, begun to be pagan by following his senses, and created a false philosophy which holds that natural things can be true causes. He says that these ideas are from the Evil One, and are only to take away true worship from God. (174) They take away true worship from God because he says we should worship what can make us happy. (170, 174) This is because, to him, all causality is from God, so all happiness is from God. But if one says that things are causes in themselves, then they can make us happy to an extent, and therefore must be worshiped to that extent. (170) Since, according to Christianity, one should not worship anything but God, this philosophy of forms cannot be correct. (174)

A Short Critique

This idea that causality is a prerogative of the divine nature leads fundamentally leads Malebranche into error, namely God must be the cause of good as well as the cause of evil. He tries to back up his argument by quoting scripture, again, not really with philosophy. He uses the Old Testament, and says that God commands the Israelites to worship Him alone because He is the only one that has the power to do good or evil to them. “He wants them to honor only Him because He alone is the true cause of good and evil, and because nothing happens in their city, according to one prophet that He himself does not cause... ” (170) This is quite a heterodox view, as to say that God willingly does evil is totally against God’s nature in Catholicism and any traditional Protestantism.

Malebranche would say in response, that it is really God executing your will. (172) But this presents a problem because is man forcing God to act? (171, 173) God would seem to be moved by man without choice. If man, in a sense, can force God to act, and can move God when he wants, then would not that mean that man has some power over God? Also, what about when man wants to do evil? If one does not posit that man is totally the cause of his own actions, then all the evil in the world that happens must be carried out by God. (174) God would be a formal cooperator in evil, and this would make God to be evil. (And again, as was said before, this would be impossible because God cannot do evil. Evil is against God’s very nature because by nature his is absolute being and goodness, while evil is the lack of existence and being and goodness.) Therefore, God would cease to be God; and then who is the one carrying out all actions and causality?

------------------

1 - Malebranche, Nicolas. “The Search After Truth" (in part). In Modern Philosophy fifth edition, edited by Forrest E. Baird, Walter Kaufmann, 166-175. New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc., 2008.

Comments

Post a Comment