Literature As Thinly Veiled Nihilistic Philosophy - A Review of "The Stranger" by Albert Camus

The Stranger

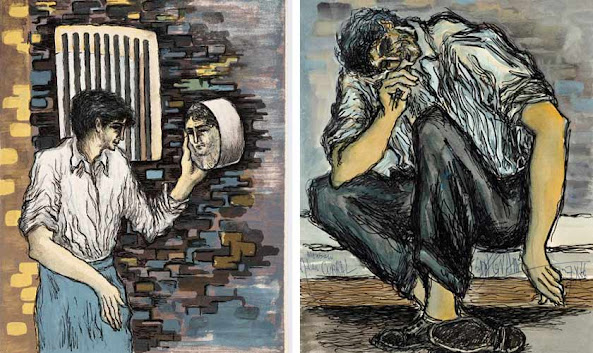

I was sorely disappointed by this book. In my opinion, it is a bad literary attempt at giving a terribly idiotic philosophy a real life expression. Camus' existentialism and absurdism is a philosophy of apathy and self-centered ego. If I had to summarize it, it would be something like this ... "Life is meaningless. Everything is all the same. If I kill a man, or I don't. If I move cities, or I don't. You want help beating up a prostitute, yeah sure why not, I'll help you. All that I really care about is smoking cigarettes and if I can hook up and get sex. I have no time for God. It's all the same anyway because we're all going to die." That may be a bit harsh to put it like that, but it's not really that different from the book. I'm honestly not sure why this book, as well as the Atheistic Existentialist philosophy, is even regarded as academic in any way. The book claims that Camus is one of the greatest French writers. That is a sad state of affairs and cannot be true.

A Brief Overview of the Story

The story itself is not that complicated, so let me give a brief overview of the plot. The main character, Meursault, is an adult bachelor living in Algiers and working a business type job. The story opens with his mother's funeral. He couldn't take care of her anymore, and so had put her into a retirement home and she had passed away. He goes to the funeral, and we first get a glimpse into his character. I would describe the main character as the embodiment of apathy. He is not necessarily that moved in any deep way by anything really.

As a reader, this does not match with my experience of life at all. Meursault, in the novel, is basically numb and apathetic to everything. He doesn't really feel any moral guilt, or even consider how he might be hurting others. "Why did you pause between the first and second shot?" I seemed to see it hovering again before my eyes, the red glow of the beach, and to feel that fiery breath on my cheeks-and, this time, I made no answer. During the silence that followed, the magistrate kept fidgeting, running his fingers through his hair, half rising, then sitting down again. Finally, planting his elbows on the desk, he bent toward me with a queer expression. "But why, why did you go on firing at a prostrate man?" Again I found nothing to reply. The magistrate drew his hand across his forehead and repeated in a slightly different tone: "I ask you 'Why? I insist on your telling me." I still kept silent." 4

I was sorely disappointed by this book. In my opinion, it is a bad literary attempt at giving a terribly idiotic philosophy a real life expression. Camus' existentialism and absurdism is a philosophy of apathy and self-centered ego. If I had to summarize it, it would be something like this ... "Life is meaningless. Everything is all the same. If I kill a man, or I don't. If I move cities, or I don't. You want help beating up a prostitute, yeah sure why not, I'll help you. All that I really care about is smoking cigarettes and if I can hook up and get sex. I have no time for God. It's all the same anyway because we're all going to die." That may be a bit harsh to put it like that, but it's not really that different from the book. I'm honestly not sure why this book, as well as the Atheistic Existentialist philosophy, is even regarded as academic in any way. The book claims that Camus is one of the greatest French writers. That is a sad state of affairs and cannot be true.

A Brief Overview of the Story

The story itself is not that complicated, so let me give a brief overview of the plot. The main character, Meursault, is an adult bachelor living in Algiers and working a business type job. The story opens with his mother's funeral. He couldn't take care of her anymore, and so had put her into a retirement home and she had passed away. He goes to the funeral, and we first get a glimpse into his character. I would describe the main character as the embodiment of apathy. He is not necessarily that moved in any deep way by anything really.

He returns from the funeral and runs into an acquaintance, Marie, at the pool and they start a random love affair and sleep together. She eventually asks if he loves her. He says he does not. She still wants to marry him. He says that he'll marry her because, well why not, even though he continues to say that he doesn't love her. He is just mostly attracted to her and enjoys hooking up. Either way, he never really thinks deeply about it all.

"You're a young man," he said, "and I'm pretty sure you'd enjoy living in Paris. And, of course, you could travel about France for some months in the year." I told him I was quite prepared to go; but really I didn't care much one way or the other. He then asked if a "change of life," as he called it, didn't appeal to me, and I answered that one never changed his way of life; one life was as good as another, and my present one suited me quite well. At this he looked rather hurt, and told me that I always shilly-shallied, and that I lacked ambition-a grave defect, to his mind, when one was in business.

I returned to my work. I'd have preferred not to vex him, but I saw no reason for "changing my life." By and large it wasn't an unpleasant one. As a student I'd had plenty of ambition of the kind he meant. But, when I had to drop my studies, I very soon realized all that was pretty futile. Marie came that evening and asked me if I'd marry her. I said I didn't mind; if she was keen on it, we'd get married. Then she asked me again if I loved her. I replied, much as before, that her question meant nothing or next to nothing -but I supposed I didn't. "If that's how you feel," she said, "why marry me?" I explained that it had no importance really, but, if it would give her pleasure, we could get married right away. I pointed out that, anyhow, the suggestion came from her; as for me, I'd merely said, "Yes." Then she remarked that marriage was a serious matter. To which I answered: "No." She kept silent after that, staring at me in a curious way.

I returned to my work. I'd have preferred not to vex him, but I saw no reason for "changing my life." By and large it wasn't an unpleasant one. As a student I'd had plenty of ambition of the kind he meant. But, when I had to drop my studies, I very soon realized all that was pretty futile. Marie came that evening and asked me if I'd marry her. I said I didn't mind; if she was keen on it, we'd get married. Then she asked me again if I loved her. I replied, much as before, that her question meant nothing or next to nothing -but I supposed I didn't. "If that's how you feel," she said, "why marry me?" I explained that it had no importance really, but, if it would give her pleasure, we could get married right away. I pointed out that, anyhow, the suggestion came from her; as for me, I'd merely said, "Yes." Then she remarked that marriage was a serious matter. To which I answered: "No." She kept silent after that, staring at me in a curious way.

Then she asked: "Suppose another girl had asked you to marry her-I mean, a girl you liked in the same way as you like me-would you have said 'Yes' to her, too?" "Naturally." Then she said she wondered if she really loved me or not. I, of course, couldn't enlighten her as to that. And, after another silence, she murmured something about my being "a queer fellow." "And I daresay that's why I love you," she added. "But maybe that's why one day I'll come to hate you. To which I had nothing to say, so I said nothing. She thought for a bit, then started smiling and, taking my arm, repeated that she was in earnest; she really wanted to marry me. "All right," I answered. "We'll get married Whenever you like.” 1

His neighbor at his apartment is a man of ill-repute, suspected of being a pimp. Either way, he has a very strange relationship with a girl who he pays monthly and has sex with. The girl wasn't spending the money he provided for her the way he wanted, and thus accused her of being false to him, or doing him wrong. The neighbor, Raymond, also had gotten into several fights with her brother (they were of Arab descent). He asks Meursault to help him write a letter to his prostitute, enticing her to come and reconcile, so he could then spring a trap on her and call her out. He ends up beating the crap out of her. So much so that the police are called, but he is let off because Meursault somehow testifies that the woman had done him wrong. Again, he doesn't think very deeply about any of this. He just kind of goes along with whatever feels good in the moment.

Eventually Raymond invites Meursault and Marie to a beach house with one of his friends. They go and are having a good time when, the prostitute's brother and another Arab follow them to the beach and confront them. They get into a fight, and Raymond has a pistol. Thankfully, the fight ends without it being drawn. Randomly, Meursault decides to go for a walk later that day back towards where the Arabs were because it was cooler over there in the shade by a little stream. For no conscious reason, other than being hot and blinded by the sun, he decides to just shoot the Arab man. He then shoots him four more times after he's dead.

"Listen," I said to Raymond. "You take on the fellow on the right, and give me your revolver. If the other one starts making trouble or gets out his knife, I'll shoot." The sun glinted on Raymond's revolver as he handed it to me. But nobody made a move yet; it was just as if everything had closed in on us so that we couldn't stir. We could only watch each other, never lowering our eyes; the whole world seemed to have come to a standstill on this little strip of sand between the sunlight and the sea, the twofold silence of the reed and stream. And just then it crossed my mind that one might fire, or not fire-and it would come to absolutely the same thing." 2

The rest of the book is Meursault being put on trial for the murder. Still, even on trial and in jail, he expressed very little emotion towards any of it. He has no remorse, and isn't even quite sure that being in jail is worse than being free. He just keeps saying how people get used to their circumstances all the same. His is convicted to be executed by the guillotine, which makes he think a bit more deeply about life, but not really. He screams at the priest chaplain that comes by, as he is an atheist and doesn't want to think about anything related to God or the afterlife because these ideas seems meaningless to him. And the book ends ...

Not So Veiled Writing and So Unrealistic

The writing of this novel is straight-forward and on the easier side. The problem, though, is that the writing is really a thinly veiled vehicle for a really terrible Existentialist philosophy. It is abundantly clear that Camus' nihilism and atheistic-existentialist philosophy is what is driving the novel, and manifests itself in all the details of the book. When I think of great literature, I think of a work that expressed the complexity of the human experience, one that is imminently relatable to the reader's own life. Such a book provides a map of implicit understanding as one lives the experiences of the characters which can help one understand their own lives in a greater context.

Not So Veiled Writing and So Unrealistic

The writing of this novel is straight-forward and on the easier side. The problem, though, is that the writing is really a thinly veiled vehicle for a really terrible Existentialist philosophy. It is abundantly clear that Camus' nihilism and atheistic-existentialist philosophy is what is driving the novel, and manifests itself in all the details of the book. When I think of great literature, I think of a work that expressed the complexity of the human experience, one that is imminently relatable to the reader's own life. Such a book provides a map of implicit understanding as one lives the experiences of the characters which can help one understand their own lives in a greater context.

The constant philosophy which inspires the narrative of this book is one that claims that there is no objective meaning to anything in life. Life is absurd and the only meaning that can be found is the little meaning that I assign to things. So whether traditionally "good" or "bad" things happen to me, they are of little meaning to me as they are random. "Still, there was one thing in those early days that was really irksome: my habit of thinking like a free man. For instance, I would suddenly be seized with a desire to go down to the beach for a swim. And merely to have imagined the sound of ripples at my feet, the smooth feel of the water on my body as I struck out, and the wonderful sensation of relief it gave brought home still more cruelly the narrowness of my cell. Still, that phase lasted a few months only. After-ward, I had prisoner's thoughts. I waited for the daily walk in the courtyard or a visit from my law-yer. As for the rest of the time, I managed quite well, really. I've often thought that had I been compelled to live in the trunk of a dead tree, with nothing to do but gaze up at the patch of sky just overhead, I'd have got used to it by degrees. I'd have learned to watch for the passing of birds or drifting clouds, as I had come to watch for my lawyer's odd neckties, or, in another world, to wait patiently till Sunday for a spell of love-making with Marie." 3 All one can do is to become accustom to them and enjoy any momentary pleasures that present themselves.

As a reader, this does not match with my experience of life at all. Meursault, in the novel, is basically numb and apathetic to everything. He doesn't really feel any moral guilt, or even consider how he might be hurting others. "Why did you pause between the first and second shot?" I seemed to see it hovering again before my eyes, the red glow of the beach, and to feel that fiery breath on my cheeks-and, this time, I made no answer. During the silence that followed, the magistrate kept fidgeting, running his fingers through his hair, half rising, then sitting down again. Finally, planting his elbows on the desk, he bent toward me with a queer expression. "But why, why did you go on firing at a prostrate man?" Again I found nothing to reply. The magistrate drew his hand across his forehead and repeated in a slightly different tone: "I ask you 'Why? I insist on your telling me." I still kept silent." 4

...

"Of course, I had to own that he was right; I didn't feel much regret for what I'd done. Still, to my mind he overdid it, and I'd have liked to have a chance of explaining to him, in a quite friendly, almost affectionate way, that I have never been able really to regret anything in all my life. I've always been far too much absorbed in the present moment, or the immediate future, to think back." 5

He only seems to consider the path of least resistance in each moment. What this turns into is a philosophy which is self-centered. All that matters is if I can obtain some momentary pleasure for myself from this situation or person. He enjoys the sex with Marie. He enjoys his cigarettes. He mildly enjoys Raymond's friendship. But any longer term thinking about moral questions doesn't seem to register to him.

He only seems to consider the path of least resistance in each moment. What this turns into is a philosophy which is self-centered. All that matters is if I can obtain some momentary pleasure for myself from this situation or person. He enjoys the sex with Marie. He enjoys his cigarettes. He mildly enjoys Raymond's friendship. But any longer term thinking about moral questions doesn't seem to register to him.

And so the experience of the main character in the book comes off as faux and insincere compared to real life. No one lives as if nothing matters to them. No one lives as if every outcome is the same as every other outcome, as long as I made the choice for that outcome. Just because we all will die one day doesn't make life meaningless. And that's the problem with Camus and Sartre; they categorically reject any notion of God or spirituality for no other reason than they can choose to do so. And so the same with Meursault in the story. He doesn't have any arguments against God or the afterlife to give to the priest, he just doesn't want to be bothered with thinking of such things.

There are two times in the book where Christian characters are devastated that he doesn't believe or care about God. Camus presents them as being something like a weakling, while his character is the brave hero who recognizes that nothing matters. The others are too afraid to consider such a state of affairs.

"Nothing, nothing had the least importance, and I knew quite well why. He, too, knew why. From the dark horizon of my future a sort of slow, persistent breeze had been blowing toward me, all my life long, from the years that were to come. And on its way that breeze had leveled out all the ideas that people tried to foist on me in the equally unreal years I then was living through. What difference could they make to me, the deaths of others, or a mother's love, or his God; or the way a man decides to live, the fate he thinks he chooses, since one and the same fate was bound to "choose" not only me but thousands of millions of privileged people who, like him, called themselves my brothers. Surely, surely he must see that?

Every man alive was privileged; there was only one class of men, the privileged class. All alike would be condemned to die one day; his turn, too, would come like the others'. And what difference could it make if, after being charged with murder, he were executed because he didn't weep at his mother's funeral, since it all came to the same thing in the end? The same thing for Salamano's wife and for Salamano's dog. That little robot woman was as "guilty" as the girl from Paris who had married Masson, or as Marie, who wanted me to marry her. What did it matter if Raymond was as much my pal as Céleste, who was a far worthier man? What did it matter if at this very moment Marie was kissing a new boy friend? As a condemned man him-self, couldn't he grasp what I meant by that dark wind blowing from my future? . .. " 6

Every man alive was privileged; there was only one class of men, the privileged class. All alike would be condemned to die one day; his turn, too, would come like the others'. And what difference could it make if, after being charged with murder, he were executed because he didn't weep at his mother's funeral, since it all came to the same thing in the end? The same thing for Salamano's wife and for Salamano's dog. That little robot woman was as "guilty" as the girl from Paris who had married Masson, or as Marie, who wanted me to marry her. What did it matter if Raymond was as much my pal as Céleste, who was a far worthier man? What did it matter if at this very moment Marie was kissing a new boy friend? As a condemned man him-self, couldn't he grasp what I meant by that dark wind blowing from my future? . .. " 6

--------------------

1 - Camus, Albert. The Stranger. (Vintage Books Inc. 1946). (52,53,54)

2 - (72)

3 - (95)

4 - (84)

5 - (126, 127)

6 - (152, 153)

Comments

Post a Comment