Our Vision for Our Lives - "Man Has No Nature" Excerpts from "History as System" by Jose Ortega y Gasset

Man's Transcendent Nature

In these excerpts from Gasset's History as a System chosen by Walter Kaufmann, Gasset is reflecting on the nature of man. As the Existentialist he is (Not one who rejects metaphysics, but finds a synthesis), he expresses a metaphysical truth in a new way. Yes man has a spirituality and a nature, but from another perspective he does not ... this is the perspective of freedom and action. Man has the ability, and actually must, create a vision for himself into who he will become. All of our choices are based on the strength or weakness of our vision for our lives, the narrative and story of who we are. And so we are these unique centaurs of existence, bound by it and yet bound by our own choices in shaping our lives.

-------------

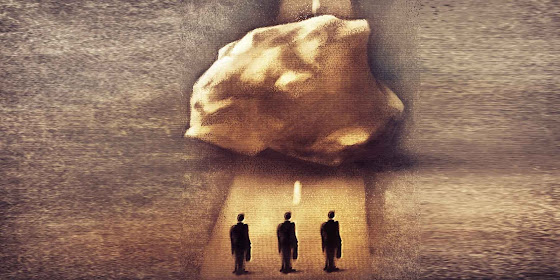

He begins by pointing out that non-human entities, like rocks have a set nature to them, while man does not have this in the same way. Our lives are, to a certain extent, in our own hands and actions. 1 Yes, there is a part of us that is like the rock, but also a part not like it. "... man's being and nature's being do not fully coincide. Because man's being is made of such strange stuff as to be partly akin to nature and partly not, at once natural and extra-natural, a kind of ontological centaur, half immersed in nature, half transcending it." The part of us like the rock, our natural side, follows the laws of nature, realizing itself in the fulfillment of its bodily needs and desires. Yet, the non physical part of us is something which is always unfulfilled, something which is always calling us to more, to the pursuit of a larger vision for our lives. We naturally consider this to be our true selves, not our bodies. And yet Gasset makes clear here that he is not talking about some Hegelian spirit moving within us.

This truest self is something of a not-yet, a thing to be fulfilled. And so we begin life as a potentiality with regard to this highest meaning of our lives. "If the reader reflects a little upon the meaning of the entity he calls his life, he will find that it is the attempt to carry out a definite program or project of existence. And his self- each man's self - is nothing but this devised program. All we do we do in the service of this program." 2 And so man must face himself as a cause of himself. Not causing himself to be, but in causing himself to be this or that man. By making this choice, one foregoes another choice, and this takes place moment after moment. But why does one shape himself by his actions in this way and not another? "...because doing this is what is most in accordance with the general program he has mapped out for his life, and hence with the man of determination he has resolved to be. This vital program is the ego of each individual, his choice out of divers possibilities of being which at every instant open before him."

The circumstances of life are present to us, yet the program that we follow into who we become is created by us or those we are around. 3 "Whether he be original or a plagiarist, man is the novelist of himself." Likewise, we have a freedom that we cannot renounce. Rather, this potentiality of life is something that everyone must face. These programs of life, though, are not fully final. We may go through many stages or adaptation and revision in this process. "Man invents for himself a program of life, a static form of being, that gives a satisfactory answer to the difficulties posed for him by circumstance. He essays this form of life, attempts to realize this imaginary character he has resolved to be. He embarks on the essay full of illusions and prosecutes the experiment with thoroughness. This means that he comes to believe deeply that this character is his real being. But meanwhile the experience has made apparent the shortcomings and limitations of the said program of life. It does not solve all the difficulties, and it creates new ones of its own." In each of the revisions we learn something and we take with us parts of the past molded into the new. It is a type of personal dialectic, the dialectic of our own history and life. 4

This is true also on a larger scale of humanity as a whole. It is our history and past actions which shape our experiences as a species. They guide us into the future of what we will become. In Gasset's words we have less a fixed nature than a fixed history which shapes us. This history expresses the rational narrative or worldview we have set for ourselves, and our dialectic process in seeking to become that man we have envisioned.

---------------------------

1 - Kaufman, Walter. Existentialism: From Dostoyevsky to Sartre. Jose Ortega y Gasset. "History as a System," Excerpts. Pg. 153

2 - 154

3 - 155

4 - 156

5 - 157

6 - Ortega y Gasset. History as a System and Other Essays Toward a Philosophy of History (1961), translated by Helene Weyl. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.: pp. 111-113, 201-203, 215-217.

Comments

Post a Comment