Persevering Through Dark Times - "Toward a Fateful Serenity" - Essay by Jacques Barzun

Toward a Fateful Serenity

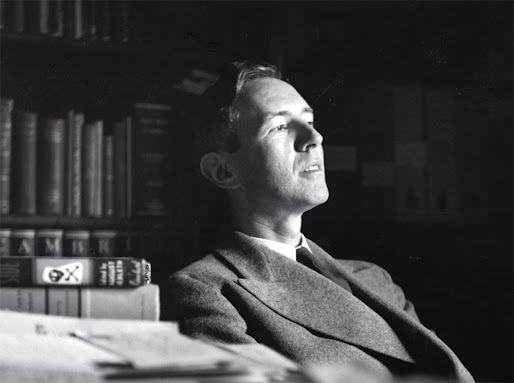

In short, this is a brief essay from the famous 20th century historian Jacques Barzun. He is reflecting on the necessity of knowing history if one is to survive the trials of one's own time. Likewise, when one is able to develop of large vision for the purpose for one's life it provides a buffer against the tragedies that life undoubtedly brings. Finally, he talks about his work to fight against a mechanistic view of the world in which creativity, uniqueness, free will, and free thought are lost.

La Belle Epoche

Barzun begins this thoughtful essay with a reflection his childhood in Paris before the First World War. He talks about it as a time of creativity, of living in the present to the fullest, a time with purpose and drive in living. Then the war happened ... and the confidence in the purpose of life turned into grief and chaos. Even as a child the effects of the war on those around him took a deep toll on his own psyche and outlook, to the point where his parents took him out of Paris to the coast to ease his mind. 1

"The outbreak of war in August 1914 and the nightmare that ensued put an end to all innocent joys and assumptions. The word Never took on dreadful force. News of death in every message or greeting, knowledge that cousins, uncles, friends, teachers, and figures known by repute would not be seen again; encounters at home and in the street or schoolyard with the maimed, shell-shocked, or gassed, caused a permanent muting of the spirit." 2

Barzun's depression with life was lifted with the reading of Hamlet while he was at the shore. Why Hamlet, one might ask? He says that in Hamlet he saw a reflection of his own situation. Hamlet was surrounded by corruption, lies, deceit, and hatred, and yet he persevered in fighting these things even in dark times. In Barzun's words, "My bewilderment and pain were transmuted by a story into a kind of armor. Later reverses of fortune could bruise but not wound. Being thus reduced in strength and rank, such vicissitudes have no place here." 3

Barzun makes the point, though, that everyone's life faces such chaos to a degree; every time period struggles with such things. In the face of this chaos, all we can do is to set out vision of life and continue to push forward in that vision. "In any age, life confronts all but the most obtuse with a set of impossible demands: it is an action to be performed without rehearsal or respite; it is a confused spectacle to be sorted out and charted; it is a mystery, not indeed to be solved, but to be restated according to some vision, however imperfect. These demands bear down with redoubled force in times of decay and deconstruction, because guiding customs and conventions are in disarray. At first, this loosening of rules looks like liberation, but it is illusory. A permissive society acts liberal or malignant erratically; seeing which, generous youth turns cynic or rebel on principle."

Fighting the Mechanical

Barzun's vision in response to the chaos of his time was to fight against what he called the "the mechanical." Here he is talking about a view of the world which reduces everything down to set processes like a machine which has only one set way of working and continues without conscious guidance. [I think that it is clear that he is referencing the societal forces which led Western man into self-destruction in the wars. The Marxist laws of history and Darwinian laws of nature were seen by many at this time of being movements which transcended any individual or government, forces that could not be stopped.]

"Where, then, is the enemy? Not where the machine gives relief from drudgery but where human judgment abdicates. Any ossified institution - almost every bureaucracy, public or private - manifests the mechanical. So does race-thinking - a verdict passed mechanically at a color-coded signal. Ideology is likewise an idea-machine, designed to spare the buyer all further thought. Again, 'methods' substituted for reading books and judging art are a perversion of what belongs to science and engineering: 'models,' formulas, theories. Specialism, too, turns machine-like if it never transcends a single task. The smoothest machine-made product of the age is the organization man, for even the best organizing principle tends to corrupt, and the mechanical principle corrupts absolutely." 4 Other examples of the mechanization of modern day life are the jargon based higher education system, and antipathy for history and the past.

Learning History as a Shield

Rather, Barzun says, it is the understanding of history that gives context to the events of the present. It allows one to remain detached, recognizing that such events have happened in the past. "History is concrete and complex; everything in it is individual and entangled. Reading it, mulling it over does not weaken concern with the present, but it brings detachment from the immediate and cures 'the jumps' -seeing every untoward even as a menacing, every success or defeat as permanent, every opponent as a monster of error."

History also buffers one against the group-think of the age. "A sense of 'how things go' in history - how they come and go - also protects against the worst among machines: the band-wagon. To keep from climbing on is harder than ever since that other machine, the media, has been installed. So many projects, attitudes, and 'concepts', as they are quaintly called, are launched with all the trappings of true ideas that holding aloof looks like egotism or the sulks, but it is not sulking to stare as the lemmings rush by; it is self-defense."

The knowledge of history also serves to bring to mind the good people of the past, the saints and heroes. 5 These men and women remind us that virtue and bravery is possible even in the worst times. They remind us that life itself, even in its mundane aspects, is valuable.

What Can We Do?

And so in the face of the problems of our age, what can we do, how can we act? Barzun makes the claim that it is in the local, the everyday, the mundane, one's neighbor and community that are the means by which change occurs. The large scale movements of change rarely have the desired outcomes that those in them want. 6 Knowledge of history shows us the debt that we owe to our ancestors for what they have given to us. Yet, we cannot repay them, as they are now gone. Rather, we can turn that debt of gratitude toward the needs of our neighbors living here and now.

"In a high civilization the things that satisfy our innumerable desires look as if they were supplied automatically, mechanically, so that nothing is owed to particular persons; goods belong by congenial right to anybody who takes the trouble to be born. This is the infant's normal greed prolonged into adult life and headed for retribution. When sufficiently general, the habit of grabbing, cheating, and evading reciprocity is the best way to degrade a civilization, and perhaps bring about its collapse." 7

In concluding the essay, Barzun laments our contemporary time as reflecting the war time scenes of his childhood, with so many modern day anxieties shrinking the space and wonder of life. While history can help shield us against the shock of these things, we must also welcome these things as expressions of fate and free will, as expressions of the non-mechanical aspect of life as we don't know what is going to happen. 8 But whatever our fate entails, we must develop that vision for our lives such that we can make sense of these events that befall us, so that we can bolster ourselves against their blows. So that we can keep our spirit about us without being drawn here and there with hysteria or despair. 9

----------------------

1 - Fadiman, Clifton. Living Philosophies: The Reflections of Some Eminent Men and Women of Our Time. Jacques Barzun. Toward a Fateful Serenity. (New York. Double Day, 1990). 31, 32.

2 - 31

3 - 32

4 - 33

5 - 34

6 - 35, 36

7 - 37

8 - 38

9 - 39

Comments

Post a Comment