What is Most Real? - Some Personal Thoughts on Zeno's Paradoxes

For most people today, whether they realize it or not, there is implicit in their worldview the belief that what is physical and tangible is what is most real. If we cannot touch something, it's not real to us. This certainly has to do with the influence of Methodological Naturalism on our contemporary culture, the belief that all that exists are matter, energy, and space. It seems as though the majority of scientists begin with the presupposition that everything can be reducible to their physical realities, and therefore anything that cannot be perceived in this physical mode cannot be real. (Now there is also a strong current that is challenging this. Check out the Discovery Institute) The problem is that this is a belief, not a proven reality. There can be no scientific proof that only physical realities exist, as science, by definition, can only verify physical truths, not immaterial ones. The soul, for example, is by definition immaterial and so if it could be perceived directly by science then it wouldn't be a soul. Now this is not to say that there can be no evidence of immaterial realities, but just that these realities will express themselves in the physical world indirectly.

Achilles and the TortoiseAchilles and the Tortoise - Similarly we see this paradox of lengths and motion with Achilles and Tortoise. Let’s say that Achilles agrees to race a tortoise and even gives the tortoise a head start thinking it will be an easy race. So the tortoise goes to distance 10 before Achilles starts and then Achilles goes to catch up with him. While he reaches that first distance of 10 the tortoise has already moved to a new spot, 10 + 1. So then Achilles goes to 10 + 1, but during that time the Tortoise has moved again to 10 + 1 + .05. And so on, every time Achilles catches up to the tortoises old spot the tortoise has already moved slightly farther ahead so that Achilles is always getting closer but never catches the tortoise. Therefore, motion is an illusion and we reach a similar conclusion, that there is an infinity of points between any two points.

So, again, why do we assume that the physical world is most real? This is the very belief that I want to challenge, as throughout the majority of the history of philosophy this was not the case. Why is not the immaterial primarily real with the physical world following in a secondary position? Parmenides and Zeno, in attempting to show that change is not real, actually ended up giving a compelling proof that the physical is not that which is most real. Let's look at some of Zeno's paradoxes.

The Racecourse

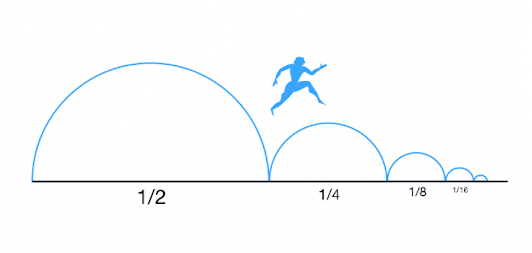

The Race Course - Suppose that you set out to run across a field to the other side. But before you can reach the other side you have to reach the mid way point of the field. But before you can reach half way you have to reach the quarter field mark. But before you can get to the quarter mark you have to reach the eighth field mark. And so on, you always have to reach halfway between the start and any point on the field. Therefore, logically you actually cannot even move from the start at all because before you can even reach the 1mm mark you’d have to first go to a half a millimeter. Therefore, all motion must be an illusion of the senses. The conclusion from this paradox is that you can divide all lengths in half infinitely. So if you only have a finite amount of time to reach the other side you’d never be able to reach it.The Archer and Arrow

The Arrow Paradox - Let’s say an archer shoots an arrow toward a target. At any given instant we look at the arrow it is in one place motionless. Therefore, logically the arrow is always altogether motionless because adding up all the instants is like adding up 0 + 0 + 0 + 0 = 0 regarding its time and motion. Therefore, logically the arrow isn’t moving because if an instant is no time then there could also be no movement. If an instant includes a duration of time then we run into the infinite distance problem between two points.Solving the Paradoxes

Zeno leads us to try and understand and define what a “point” and a “now” are. If we conceive of points (the smallest units of physical extension or space/matter) and nows (smallest units of time) as things with amount and duration then we are in trouble one way. Think about it, if a point has a physical distance to it, no matter how small, that means that a point is really a line and a line always can be divided into smaller units. If a now is an amount of time, an amount can always be divided into smaller units of time. Therefore, if we think of points and nows as having physical reality then we run into the infinite divisibility problem, how is it that there can be an infinite amount encapsulated in something finite, ie infinite points in finite space or infinite time in finite duration? On the other hand, if we say that points and nows do not have extension or duration then are they just nothing then? How does 0 + 0 + 0 = something? This too would lead us to say that everything is also an illusion and isn’t really moving.

The Intangible Over the Tangible

So what exactly is the physical changing world of matter? Well, that's exactly the point! The term matter is not a concept that can be explained with reference to the physical world. This very problem is going to force Plato and Aristotle to develop, what they called, "formal" reality. In other words, a reality which exists at the root of being. A core identity which is not equivalent to its physical parts, but represents the unified whole. It is a concept which is so deep that there is nothing more fundamental to explain it by. It is that which exists in itself, the actuality of being "what it is" in the most fundamental sense. Aristotle, in Greek, gives this the name "energia" or "entelecheia". It is a reality that we can only experience indirectly through its accidental, or physical, properties when it is embodied in prime matter, or the taking on of the mode of being equal to having parts, or quantity.

While there is not enough space in this post to unpack fully the idea of "energia," all of us know its existence and truth through our experience. Just ask yourself, are the most meaningful things to us the material things that we own or the aspects of life that we cannot touch? For example, the relationship shared in a family, helping others improve their lives, having a good conscience, the wedding vows shared between a couple, and the prayers uttered to God in the depths of one's heart. They are things which are clearly more equal to their immaterial identity rather than their physical accidents. A marriage is not about the rings or ceremony, but the meaning of the words exchanged which binds the couple for life.

I am reminded here of the Latin author, Livy's, Rape of Lucretia. While I am in no way condoning the idea of rape or suicide, the point of the story stands out to me as a stark example of what is being discussed here. Lucretia so values something that is intangible, her purity, that she is willing to give up her physical life in order to honor her spiritual existence.

A Platonic Vision of the World

When all is said and done, though, there is probably no one who believed in this more than Plato. This idea of the immaterial identity in things being more real than their accidental parts is actually similar to one of Plato's arguments for the immateriality of the soul in his work, The Phaedo. I have written on that here. Before describing it, ask yourself, what is more real ... that which decays and is destroyed or that which cannot decay or be destroyed? I think everyone would say that the thing which cannot decay, be destroyed, or be otherwise is that which is more real.

In so many words, Plato makes the argument that ideas have more an identity of immortality than physical things, and thus are more real than them. For example, 2 + 2 = 4 is an abstract idea, not a physical thing. To Plato's point, it is eternal because 2 + 2 = 4 has always existed and been true. It could not be otherwise, as it will never equal anything other than 4. And it has no parts that can decay or be destroyed, it will always continue to be the same. Compare this with a physical thing like a tree. The tree did not have to exist. In fact, at one time in the past it was not existing. It has parts that will decay and cease to exist as a tree. And this is true of every material thing. I think there is an argument to be made that the formal identity in things is that which is most real, not the physical accidents that makes things up. In a way, Plato pioneered a type of vision of the world in which the immaterial identity of things shines forth brighter than the shadows of the changing physical world.

So, ask yourself again ... What is most real?

A very insightful article. The concept that the immaterial is far more real than the material is sadly lost with most of modern man, with the majority of peoples believing that that which they feel and see are far more present than those immaterial and abstract concepts. The recognition that math falls under the abstract and not the material should help to provide an example of the immaterial that can be extrapolated to the heavenly.

ReplyDeleteIt seems supremely ironic that we are part of a culture that idolizes mathematics, yet doesn't realize that mathematical intelligibility to reality is one of the biggest arguments against the Materialist point of view!

Delete