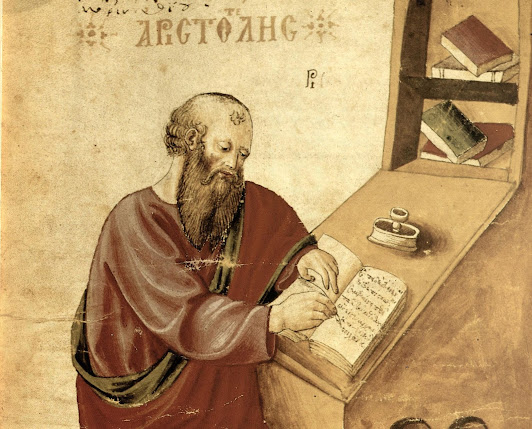

Unsolved Questions in Aristotle's Work - Some (Incomplete) Personal Thoughts

Just a quick note, this post is some incomplete thoughts that came to me as I was reading through Aristotle's Physics and Metaphysics. I haven't had the time to augment these examples with quotes, but at some point I will. Right now I just want to get my thoughts down on paper. Please forgive me if there is incorrect or inaccurate information in this post. Again, these are just some rough personal thoughts.

Connecting the Aristotelian Dots?

Aristotle is one of the greatest minds that ever lived, and reading through his works is an initiation into a new mode of being if one is able to make it through. At points, though, I was bothered because there are some parts of this great philosophical system where there aren't answers that fully satisfied me. It was like he was right on the cusp of connecting all the dots in the larger picture, but never seemed to do it. At a certain point I came to realize that Aristotle doesn't connect all those dots because he is primarily trying to explain what is, what he can observe, not provide a system wholly complete in itself which fills in all conclusions for the reader. Aristotle certainly took a more empiricist view towards things than his predecessor, Plato. And so maybe this is an expression of that tendency. His attempt at explaining reality starts from the position of the observer here and now, and moves outward into the darkness. Here are some examples of what I am thinking about:

Matter and Form as Relative Terms

For a long time I struggled with the concept of matter and form. Aristotle often uses the example of a bronze statue or a brick house to make this point between the matter of the thing and its form. The problem is that these are artificial objects where the distinction is very clear. When dealing with natural objects, the distinction becomes harder. With the help of my professor, I finally began to realize that matter and form are relative terms, depending on the level of abstraction that you consider it under. What is the form at one level of abstraction actually constitutes the matter at a higher level of abstraction. For example, hydrogen and oxygen (forms in and of themselves) become the matter which takes on the new form of water. Water then can become the material for a new form, say when creating soda. The matter - form relationship depends on the given level of abstraction.

What is Matter?

This leads to the question, though, "What ultimately is matter?" Can this matter-form relationship go on forever? Aristotle says, no, it cannot and presents a compelling theory of immaterial forms which exist at the root of the existence of things. As far as what matter is in its most fundamental form, Aristotle gives a name to it "prime matter," but doesn't seem to fully flesh out exactly what it is. Prime matter is pure potentiality to the being of a form, but it is clear that prime matter doesn't actually exist. There are only form-matter composites that exist in reality. Prime matter is a theoretical notion. But what exactly is pure potentiality? Aristotle doesn't really expand much on that, to my knowledge. There are the forms which are dependent on the mind of God, but what exactly is matter? Well, from the perspective of the empiricist, maybe it's not clear. Could the principle of matter be itself a form? This leads us into Aristotle's discussion of the nature of the universe.

The Everlasting Universe and the Chain of Being

If we follow Aristotle's method, the answer is to simply describe what exists, not to fill in all the conclusions. The ultimate origin and nature of matter is similar to the question about the ultimate origin and nature of the forms or the universe. Looking backwards, it seems that this process of decay and reconstitution of matter and form has always happened, and therefore maybe they have always just been existing in this way together. Therefore, there's no real need to explain the ultimate origin of the being of the thing. Maybe matter is co-everlasting with form. But, wait, it doesn't make sense for the universe to be everlastingly proceeding into the past and the future? It doesn't, but that is what Aristotle concludes from our experience of past, present, and future.

Likewise with Aristotle's great chain of being to the Unmoved Mover. Aristotle explains the dependence of the existence of lower being on more perfect ones but it is not a fully fleshed out notion of ontological being. This can be seen more clearly with the higher beings in the chain, the elements, celestial bodies, and unmoved movers. There's not really an explanation for how they exist, their origin, but just rather for their continued dependence of the higher in motion. Again, Aristotle gives an explanation for what is, and doesn't speculate far beyond that which makes clear the empirical starting point for Aristotle in his philosophy.

The Genius of Aquinas

It took about a millennium for someone to come along and connect the dots and flesh out the conclusions of what Aristotle proposed. This was going to be Thomas Aquinas in the 13th Century. Aquinas deepened Aristotle's notion of being to include complete ontological dependence of the lower on the higher, and the higher on the one and only highest, God. Aquinas worked this deepening in two ways. He, in one way, completed Aristotle's system on its own terms, and, in another way, showed how Christian belief was able to fill in the gaps as well.

On Aristotle's own terms of an everlastingly old universe of generation and decay of matter-form composites being pushed along by the motions of the more perfect bodies, Aquinas is able to likewise provide a deeper ontological dependence in the chain of being. Aquinas can use Aristotle's idea of the universe being everlasting and expand on it by holding that the dependence of the lower on the higher was not just in terms of motion, but in terms of fully dependency of its being. He can even justify creation ex-nihilo, not from a temporal perspective, but from a timeless ontological dependency. The lower forms, at each and every moment, and at all times depend for their continued existence a timeless dependency on the Unmoved Mover, God. Creation is a relationship of total dependency.

Likewise, he is also able to take this notion of ontological dependency and use it to explain the Christian belief that the universe is not everlastingly old, as either way the created order depends on the uncreated in a relationship of its whole being, not just its movement.

Comments

Post a Comment