Introduction

Here is a look at Meditation 2 from Descartes Meditations on First Philosophy. If you haven't read Meditation 1, please take a look here. If you are interested in my personal thoughts on critiquing Cartesian Rationalism, check here. In Meditation 2 Descartes explores a bit more regarding what it means to be a "thinking thing." In Meditation 1 he established that he must be this thinking thing. Here he makes an interesting claim, that even his perceptions of reality as a "body" must really be grounded in the existence of his more fundamental thinking mind. As such, it is the mind which perceives the essences of things, what they really are, and affirms their nature in its act of judgment.

This idea, while being more extreme than Plato, reminds me of Plato's fundamental insight ... that the mind perceives reality on a fundamentally different level than the senses do. The mind pierces down to the essences of things, while the senses only perceive the changing physical nature of things. Descartes obviously is taking this even further, claiming that the senses are somehow then faculties of the mind, cutting himself off from the direct knowledge of the bodily world in itself. By doing this, it doesn't appear clear to me that it is possible to undue such an error if one continues down the same path of Rationalism.

Another interesting introductory point is that Descartes expresses at the beginning of mediation two how he was disturbed by his first meditation the previous night and how it has unsettled him. There’s a sense for the reader that these meditations are a look into his personal diary, something akin to Dr. Jekyll Mr. Hyde or Frankenstein. He has opened Pandora’s box and it can’t be shut.

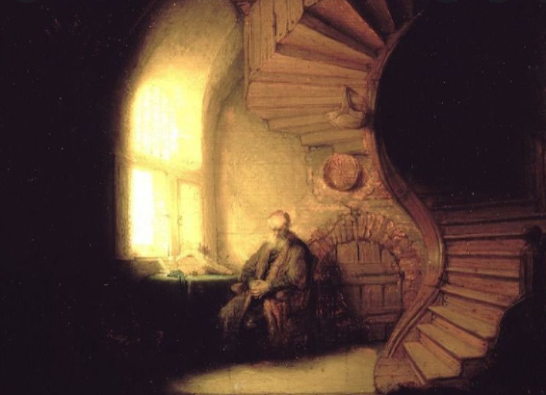

This is quite a different way to do philosophy, say as opposed to Ancient Greece. Descartes is alone secluded in his cabin having a thought dialogue with himself. How representative of the sprint of that age and the turn towards this individualistic inductive method. Socrates philosophized through dialectic, by having conversations with people at parties or in homes or on the street. It was done in relationship with others, not shut away in the seclusion of the mind.

Meditation 2

Meditation two begins the next day and he returns to his thought experiment. Descartes says that he certainly feels uneasy about it, but must continue. Anything which even has a shred of doubt to it he will consider false, thus trying to find one thing which is undoubtable, acting as a firm foundation for truth. 1"... I shall proceed by setting aside all that in which the least doubt could be supposed to exist, just as if I had discovered that it was absolutely false; and I shall ever follow in this road until I have met with something which is certain, or at least, if I can do nothing else, until I have learned for certain that there is nothing in the world that is certain. ... in the same way I shall have the right to conceive high hopes if I am happy enough to discover one thing only which is certain and indubitable." 2 Descartes then picks up where he left off in meditation one, with the idea that his whole experience of existence is a trick and he cannot trust even those things which seem clear, such as two and two make four. He has even put into doubt that the reality he perceives is what exists, that he has a body, that other people exist. The only thing he concludes that he is left with the reality that "he exists" because even if the evil demon is deceiving him with regard to everything else, he can only be deceived if he does indeed actually exists. So every time he performs the act of thinking, it is proof at least that he exists, even if everything else is a trick. 3 "Then without doubt I exist also if he deceives me, and let him deceive as much as he will, he can never cause me to be nothing so long as I think that I am something." 4 Here, he has finally found a foundation on which to proceed without doubt to whatever is true. 5

Being a Thinking Thing

Descartes then spends time reflecting and trying to figure out what exactly he is. It doesn't seem possible, given his system of doubt, to conclude the obvious reality that he is a body, for he can be deceived about this. Likewise those functions which depend on the body cannot be him either. If the deceiving demon is all powerful, and if he senses many things in dreams that aren't real, then it seems as though he cannot accept that he has a body or the functions that bodies do. What is Descartes then? The only thing he can conclude is that he is a "thing which thinks." 6"What of thinking? I find here that thought it an attribute that belongs to me; it alone cannot be separated from me. I am, I exist, that is certain." 7

The Mind Knows Reality Through the Perception of Essences

Having doubted his physical existence, he turns to his imagination. His imagination is just another expression of previous knowledge of the physical world, of which "... all things that relate to the nature of the body are nothing but dreams and chimeras." 8 Thus one cannot proceed in knowledge of the world through the use of imagination. Rather, the mind must proceed by other means towards truth, free from imagination. So what does it mean to be a thing that thinks? Is there anything more that can be known with the same level of certainty? 9 Descartes then understands that even if the content of his imagination is false, the fact that he imagines cannot be false. It, as a power, must be part of his thinking self. He attributes the same to feeling sensations. It may be that his sensations of the world are false, but the fact that he feels not false. It, too, must be part of his thinking self. Descartes then moves to an example to make his point. He talks about a ball of wax. Taken right from bees, the wax has many qualities which might, at first, seem to be essential to it. It smells fragrant, sweet, hard to the touch, colorful. But when moved closed to a fire all these qualities disappear, and all that's left is essentially a flexible extended body. 10 "Certainly nothing remains excepting a certain extended thing which is flexible and movable." 11

What then really is the basic content of imagination? Extension and shape? But even these can be extended infinitely beyond man's imagination into shapes and numbers beyond picturing. Thus, at its deepest core, a thing is known by the intuition of the mind as to its essence. 12

"But what must particularly be observed is that its perception is neither an act of vision, nor of touch, nor of imagination, and has never been such although it may have appeared formerly to be so, but only an intuition of the mind, which may be imperfect and confused as it was formerly, or clear and distinct as it is at present, according as my attention is more or less directed to the elements which are found in it, and of which it is composed." 13 This intuition of mind of the essence of a thing is not something which is directly understood in perception, i.e. seeing it, but rather something which is aided by sight but must be determined by the act of judgement by the mind in affirming this thing to be what it is.

In so many words this is Plato’s point in The Phaedo with his idea that knowledge is recollection. That somehow the physical data can never add up to the essence which the mind perceives and thus the mind must have these essences innate within it.

Thus what is most clear is that he exists as a thinking thing, that each of his senses affirms the reality of himself as a thinking thing, and that if there is to be a reality in things, it is a reality that is understood and perceived by the mind on a rational level based off the mind's judgment about the nature of the thing, not its physical perceptions. 14

|

| Instead of the PreSocratics looking out at Nature and seeking what is most real in being, Descartes diverts philosophy to look for what is true, meaning philosophy is about certainty in the mind. |

"I see that without any effort I have now finally got back to where I wanted. I now know that even bodies are not strictly perceived by the senses or the faculty of imagination but by the intellect alone, and that this perception derives not from their being touched or seen but from their being understood; and in view of this I know plainly that I can achieve an easier and more evident perception of my own mind than of anything else. But since the habit of holding on to old opinions cannot be set aside so quickly, I should like to stop here and meditate for some time on this new knowledge I have gained, so as to fix it more deeply in my memory." 15

----------------------

1 - Fieser, James and Samuel Stumpf. Philosophy A Historical Survey With Essential Readings. Rene Descartes. Meditations on First Philosophy. pg 152

2 - 152

3 - 152

4 - 152

5 - 152

6 - 153

7 - 153

8 - 154

9 - 154

10 - 155

11 - 155

12 - 156

13 - 156

14 - 156

15 - 156

Comments

Post a Comment